在 2023 年这个时间点,我看不出有什么继续使用豆瓣标注功能的理由(社交功能另说)。NeoDB 在各方面都优于豆瓣。

- 无审查。最直接也是最重要的原因。豆瓣被删去的条目太多了,比如最近大火的《人选之人:造浪者》 。没有人想读了一堆书看了一堆电影,结果标记不上吧。

数据来源更丰富。比如 NeoDB 可以标记播客,未来还会支持更多豆瓣没有的条目类型。

代码 和 roadmap 都开源。网站是 Django 写的,小问题完全可以自己改。

社区友好。GitHub Issues 回得快修得快,还有 Discord 社群。你知道怎么向豆瓣提反馈吗?反馈了会听吗?

- 无痛迁移。可以直接从豆瓣把数据导入 NeoDB,参考 NeoDB使用指南。

使用 NeoDB 并不需要你使用 mastodon,只需要你有一个账号。所以即使你不用 mastodon,也完全不影响使用 NeoDB。

豆瓣就像一艘沉船,如果你还在用,NeoDB 大概会是你的救生艇。

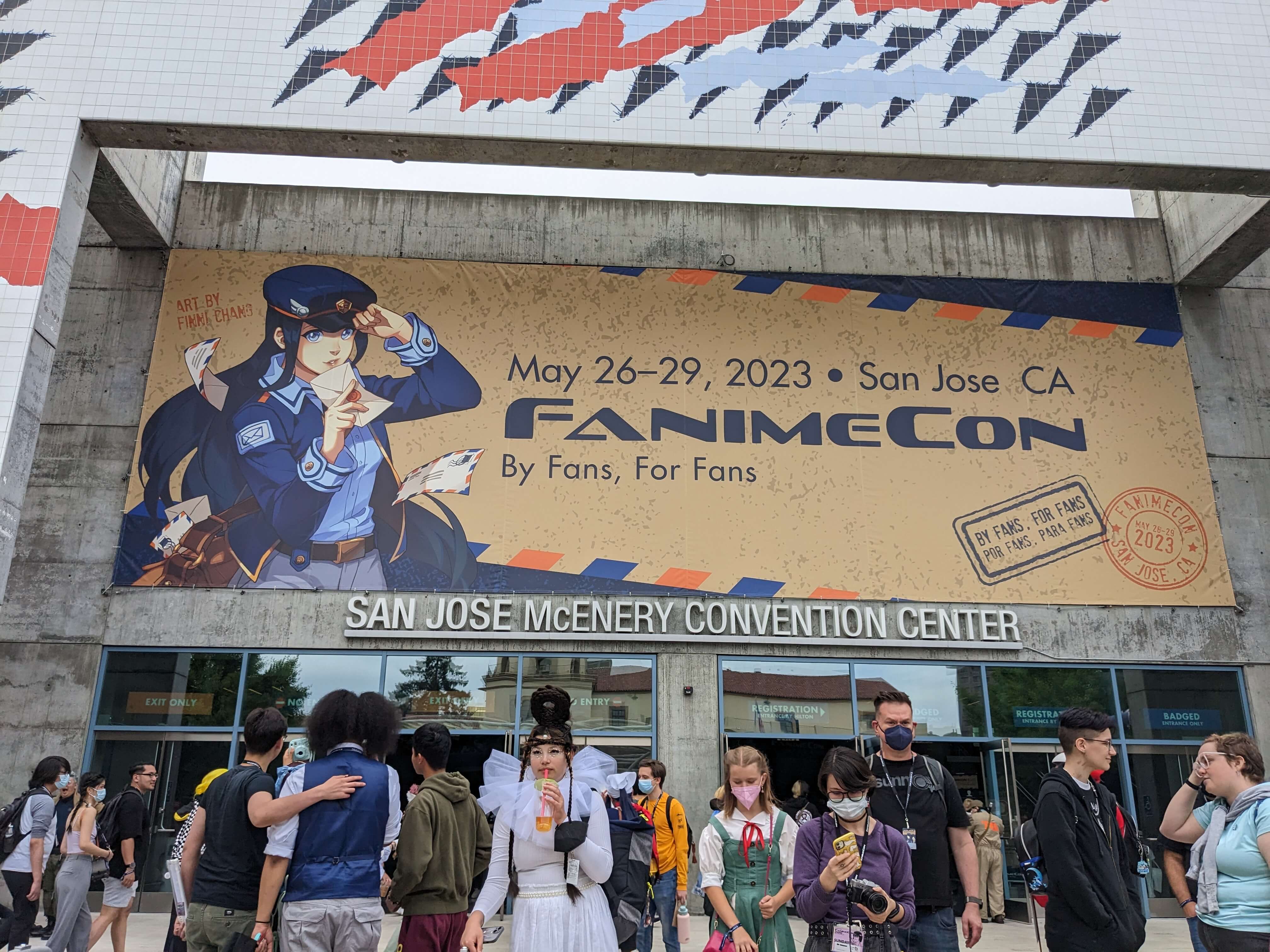

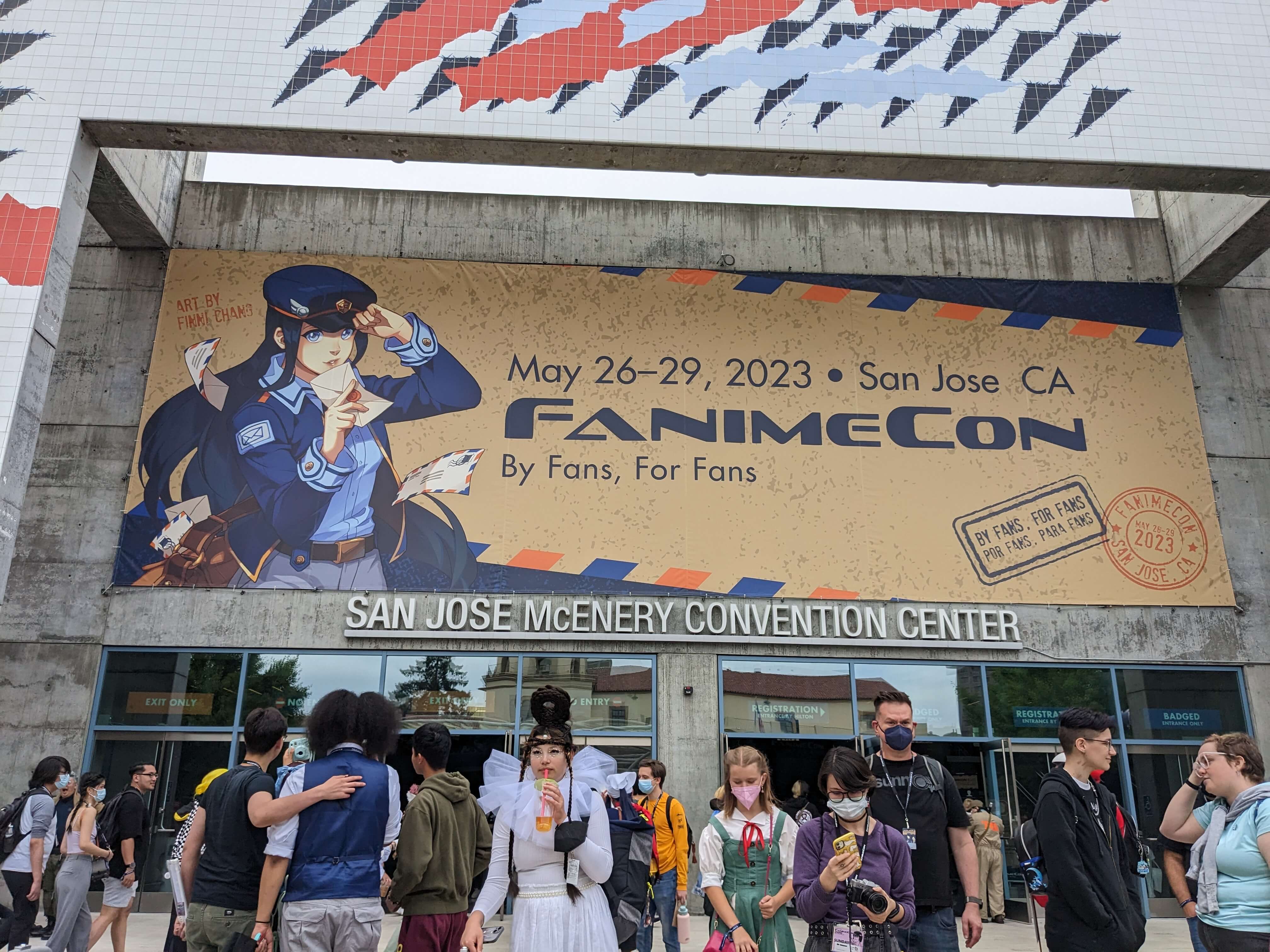

这两天去了 FanimeCon。第一次参加美国漫展有不少新鲜的体验,趁记忆还热乎记录一下:

之前印象流,以为美国漫展主要都是漫威DC啥的。FanimeCon 完全颠覆了这个印象:我几乎看不到任何美漫角色的 cos 和周边,全是你能想到的那些新番+热门民工漫,还有原神。题材而言,和国内漫展没有任何区别。

原因为何?或许 FanimeCon 传统上更偏向日本 ACG,但我觉得更可能是 Crunchyroll, Netflix 等流媒体的发展打破了国家和语言壁垒,让美国观众得以同步观看新番,因此观众数量大爆发。Gigguk 以前探讨过这个现象,说现在追番的潮流太吓人,观众都仿佛 FOMO(fear of missing out)一样只看当季新番,反而没有以前那种”新宅入门必看xxx部作品“一样重视优秀老番的风气了。再有就是湾区亚裔多,可能是日本动漫人气碾压的另一个原因。

那什么作品最热门呢?单从 coser 比例来说,原神 tier 1,电锯人 tier 1.5,其它各种作品的角色都有人出,但比例没法比。祝贺米哈游和中山龙(还有藤本树)

说到 coser,和国内漫展有个很大区别:美国的 coser 巨多,简直人均 coser。可能美国人就是更愿意展示自己吧。然而摄影师是真的少,全场没几台单反,完全见不到国内和日本那种长枪短炮怼着 coser 拍的场景,基本就是路人问 coser 要合影拿手机拍这样。不少还不错的 coser 甚至都没啥人拍,有点可惜。

要问哪个 coser 最亮眼,无疑是这位老哥,cos 的是塞尔达王国之泪里的角色。观众如果像游戏里一样帮忙举着让牌子不倒,老哥就会给你一个红色小石头(游戏里的钱)+ 小零食(蘑菇饭团)+ 贴纸(礼物),很有交互感XD。这位 coser 也是刷爆 Twitter。

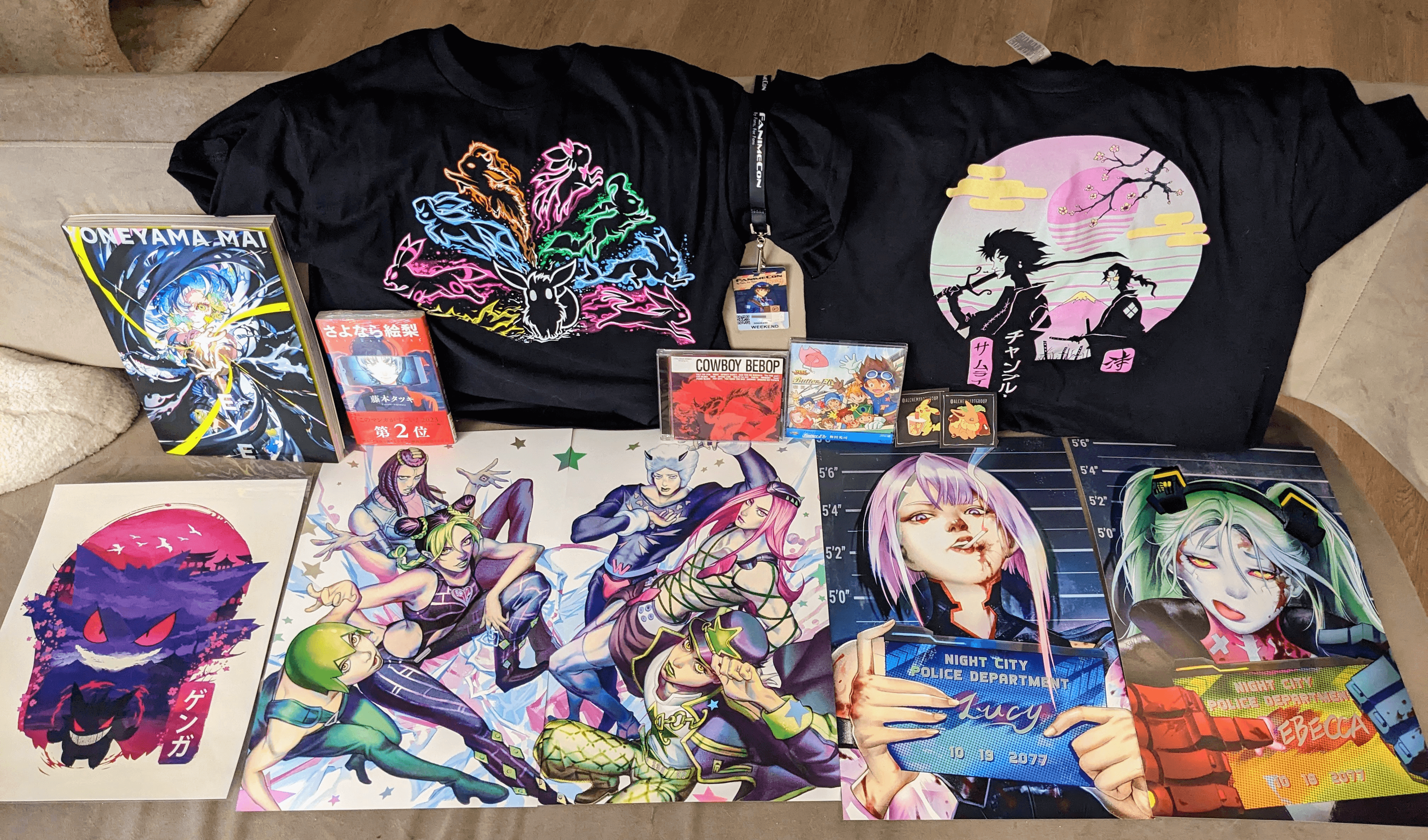

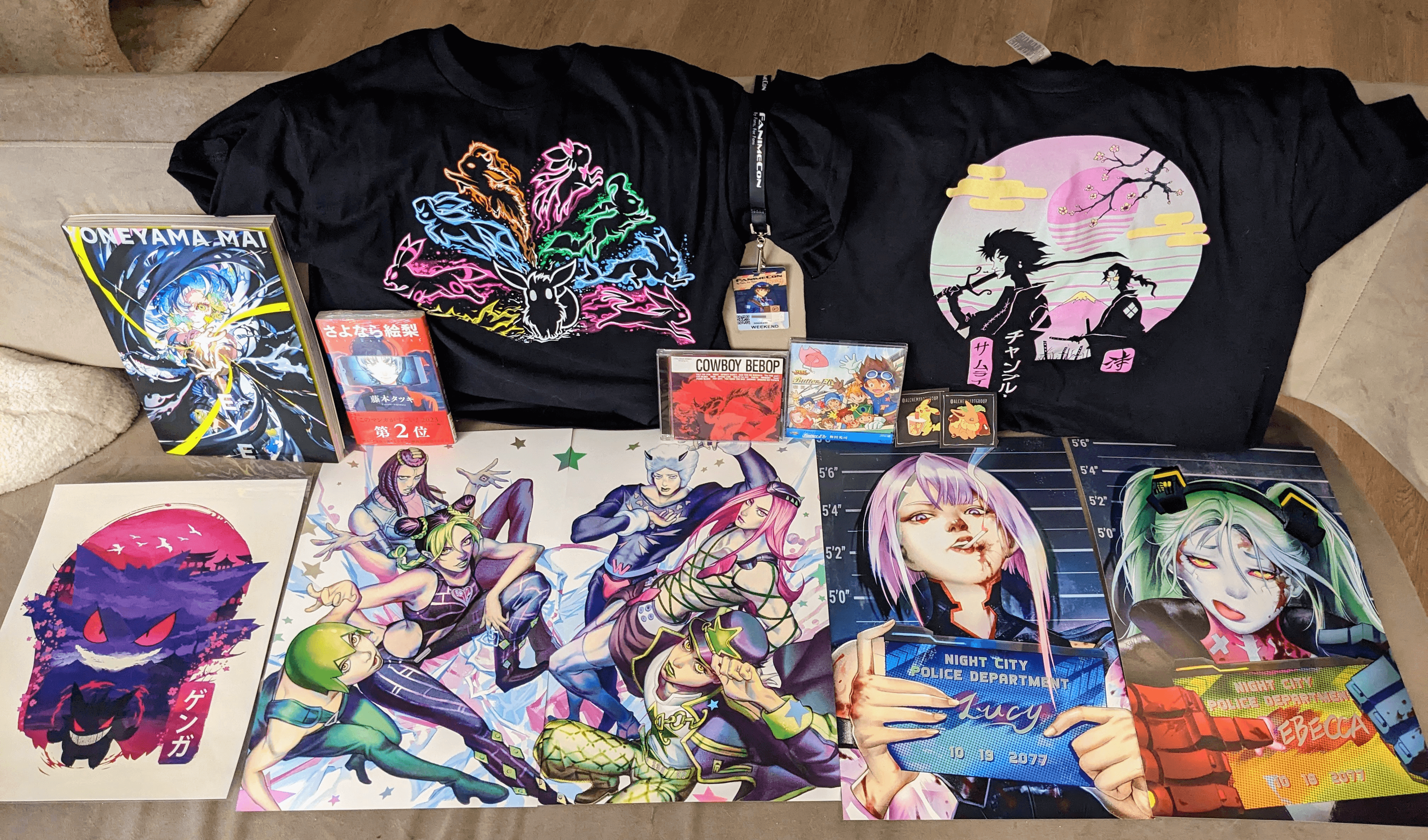

很高兴看到了很多星际牛仔的周边,这都多少年了,美国人看来是真的喜欢。还有一个死亡笔记和星际牛仔真人版哪个最差的投票,笑死我了。星际牛仔真人版我真的觉得还 OK。

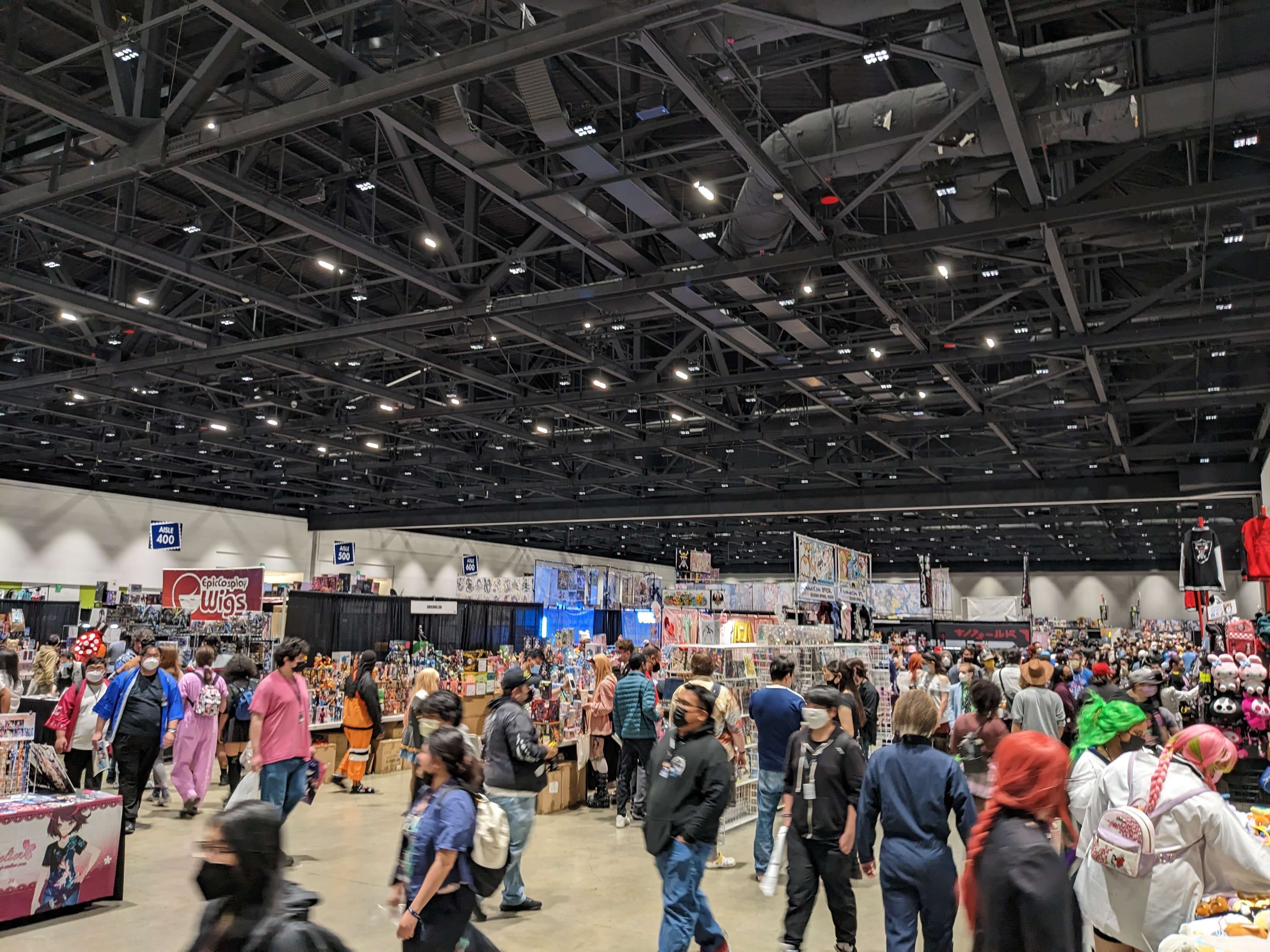

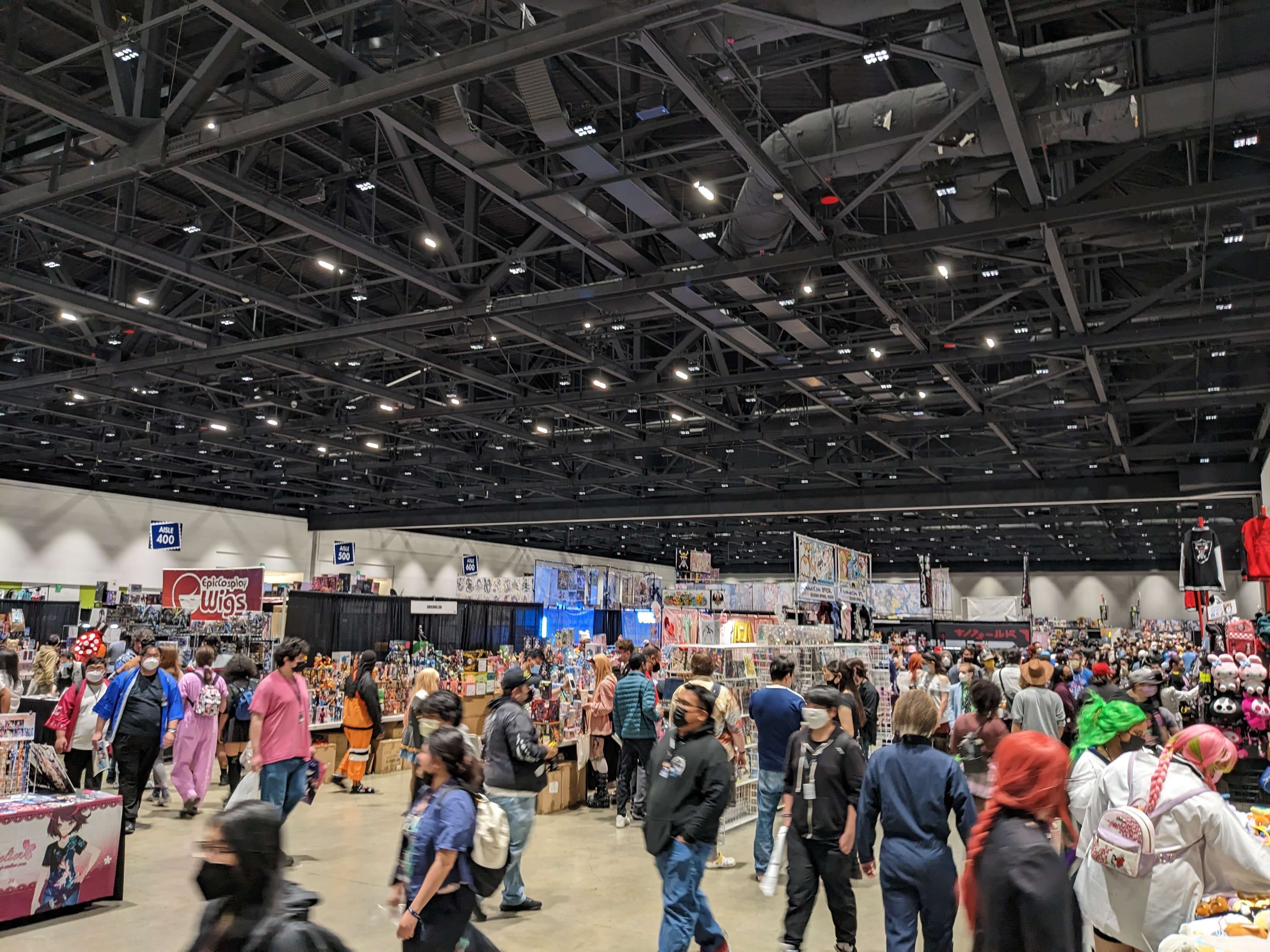

会场是在一个会议中心,主要有几个区域:商品贩售(商家),画师卖画,游戏。商品贩卖区算是中规中矩,并没有很大,见下图:

画师展厅每人有个小摊位,挂满了自己的作品。我也买了一些(后面有照片),逛得还挺爽的。

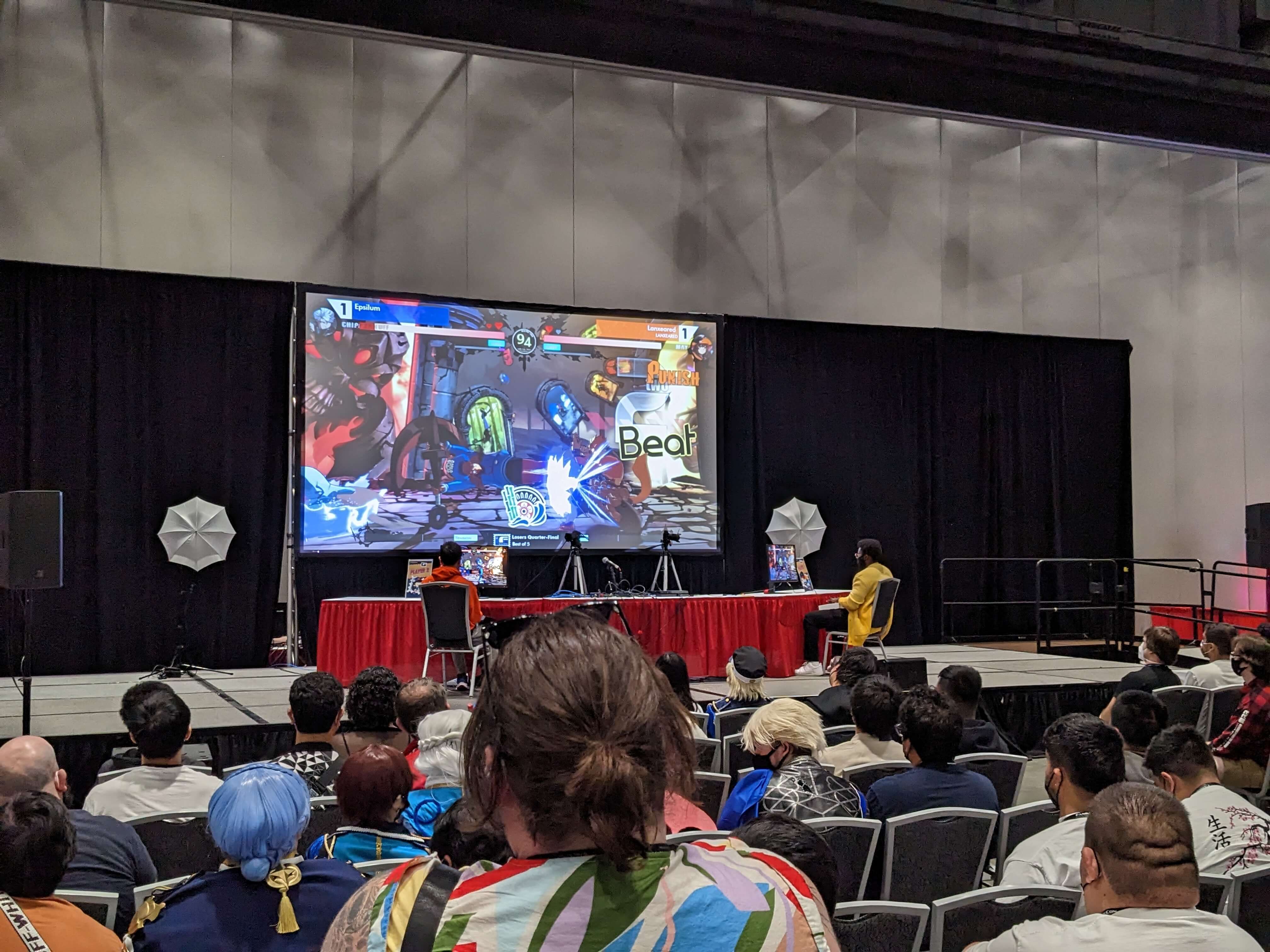

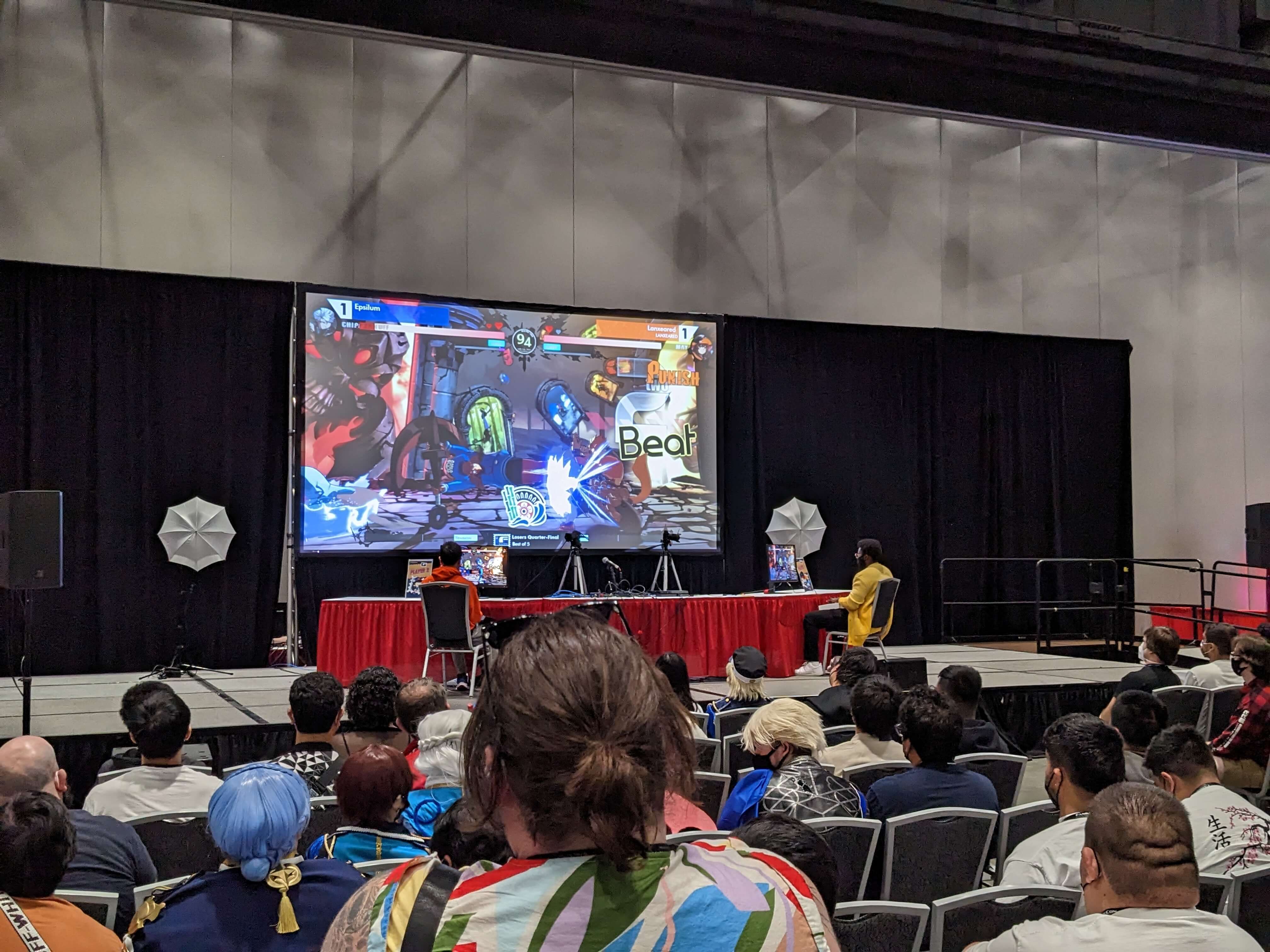

比较有特色的是游戏区,有比赛区、街机区、桌游区、甚至还有一个网吧。很多人在那边玩各种游戏。照了一张罪恶装备的比赛现场。这是我第一次现场看格斗游戏比赛,观众还是非常激动的,当然我完全看不懂:)

还有很多五花八门的活动,我甚至只来得及去一小部分。像什么 coser 比赛,女仆咖啡厅,影片放映我都完全没去,甚至还有 speed dating 和舞会😅。主舞台较小,但也有各种表演(见视频),最后一天下午甚至全是 Kpop,观众可以上去跳。

- 我去过的会议里(主要是编程相关和漫展),FanimeCon 不论是会场、官网、组织,还是流程都是绝对顶级。可能也只有规模更大的 San Diego Comic-Con 和 Comiket 能超过了吧,但我还没去过这俩。

- 比较遗憾的是,活动结束后才知道在另外一个会场(需要从主会场搭班车前往)有专门的 R18 主题的展会(Silver Island),时间也不是白天而是晚上。逛贩售区的时候我还在想美国漫展咋这么保守,没想到竟然在分会场,可以说很有美国特色了。没事,还有明年。

- 另外两个遗憾

- 画师展厅有一个玛奇玛的图特别好,只可惜卖完了,还不能预购

- 见到了 cos 京子和国夫的一对 coser,犹豫了一下没拍照。热血少女系列两作我都很喜欢,这种小众作品的 coser 还挺难见到的,真的应该拍一下的。

疫情三年,很多活动要么转线上要么停办,比如 PyCon US/China, PyCascades。后疫情时代第一次参加线下活动,真的是久违了(FanimeCon 要求疫苗证明+全程口罩,想不到吧)。查了一下才知道,FanimeCon 历史非常久,前身可以追溯到 1994 年开始的 Central Valley Anime Expo。明年(2024)是 FanimeCon 三十周年,想必活动规模也会更大,可以好好期待一下。

最后的最后,当然是晒一下战利品了,并没有买很多:

和很多打工人一样,个人开发也是我的理想。我有一个“想法清单”,从几年前就开始把想到的东西放进去,现在已经存了不少。

当我开始认真地想这件事,我意识到相比做什么,先决定“怎么做”更加重要。因此我列了一下感觉比较重要的几点,一方面是定下基调以此来决定接下来要做什么,另一方面也想接收一些反馈,毕竟我也明白这些想法可能很幼稚。

- 做自己需要或者感兴趣的东西

这条估计很多人不认同。但作为一个兴趣导向的人,我很难逼自己用业余时间去做自己不感兴趣的东西。况且如果自己喜欢,应该也能找到有相同想法和喜好的人。

- 让人们的生活或者这个世界变好,即使只有一点点,起码不能变坏

- 低维护成本

考虑到我有全职工作并且暂时不打算辞职,必须保证项目能以低成本维护

- 明确目标

既要又要是困难的,因此需要在开始前就明确目标。我觉得可能有以下几个维度:

- 不需要投资 (self-funded),至少在需要 scale up 之前

- Start small

我会避免使用“创业”(entrepreneur)这个词,因为它反而限制了你能做的东西,甚至规定了你要怎么做,而这是我不喜欢的:

- 项目要快速上线,快速迭代

- 项目一定要有 PMF(虽然这点我其实是认同的,也想尽量做到)

- 项目要能赚钱,最好还是赚大钱

- 项目要能 scale,要有想象空间

- 要全职,不成功便成仁

在这点上,Sahil 和 Gumroad 的创业故事给了我很大启发,比如著名的 No Meetings, No Deadlines, No Full-Time Employees。如果你还没读过,建议一读。

顺便推荐一个播客《硬地骇客》