See Hacker News discussion

I work in Google Ads in the past several years. Over time, I've seen one pattern came along again and again, causing endless pain for developers, that is, creating mini-frameworks.

What is mini-framework?

First, I'd like to give readers a sense of what I mean by "mini-frameworks". Imagine a company with 1000 engineers, and they share the same tech stack. Over time, a team finds the shared tech stack unsatisfactory, either because they have to write boilerplate code over and over, or the performance is not good enough, or whatever. So they decided to create their own framework on top of the shared stack. You know it's a framework and not just a library, when you hear engineers present the work using concepts & terminologies they invented, as a way to actualize their mental model. Framework like this is what I called "mini-framework", with some common characteristics:

- Created by a small number of team(s) to solve their pain points

- Wraps around the company/org-shared tech stack or framework

- Invents new concepts & terminologies that didn't exist before

- Creators claim that the framework "magically" solves many problems, and push more people to use it

If you work for a big company, most likely you've seen or even done this. But why is it bad? Being a victim myself, I can share my story.

My Story

Over the years, my team has been using a Google-internal framework to write server code, and are gradually migrating our org's codebase onto it. This framework is well-designed and maintained by a dedicated team. We're generally happy with it, though it has some itchy points (not pain points). Being a strong and ambitious engineer, my manager proposed that we add an abstraction layer on top of it, with the aim to lower the barrier for org adoption, and solve those itchy points on the way. I was skeptical and tried convincing my manager not to do it, but failed. Eventually, several engineers spent quarters to add this abstraction layer, and now the fun begins.

First, one author tried to adopt it in our existing codebase. People thought it would be easy, but it took like a year. Why? Because during the migration, they found that the abstraction cannot handle certain use cases, so they have to spend time patching it to make it work. In the meantime, other people like me were writing new code using the original framework, this again added new requirements and workload for migration. Eventually, after spending way more time than initially planned, the migration completed, and my manager decided that newly-written code should use our own framework.

You think this is the end? Of course not!

Since I started writing code with the new framework, there wasn't a single time that I didn't want to curse and quit the job. The framework is so hard to use, it introduced so many concepts with the intent to hide complexity, but ended up bringing more. Since I'm not the person who writes it, I'm not familiar with all tricks and hacks. As a result, what used to cost me a day to finish can now take two weeks, plus I have to constantly ask the author how to do certain things, and even booked pair-programming sessions. As I heard, other team members were having the same complaints. As for the original goal of driving adoption, ofc it didn't help (if not making things slower). What's funny is that, this layer is supposed to make people outside of our team write code more easily, but now even our own team are suffering from it.

Looking back, part of the problem was caused by bad design and implementation, but the fundamental problem lies in creating the mini-framework in the first place. I've observed other mini-frameworks, they all sort of have the same problem, just some worse than the others. So I've come up with a few thoughts to explain why mini-frameworks are bad.

Why mini-frameworks are bad?

First, mini-frameworks lacks feature completeness and compatibility. People often think that they can magically "hide the unnecessary complexity", but in reality they can't. Even if the mini-framework can deal with 80% use cases well, they often lack the flexibility and features from the original framework to satisfy the rest 20%. DSL (Domain Specific Language) shares the same problem, and that's why people hate it so much.

Second, mini-frameworks violates the ETC (Easier To Change) principle. I first learned the concept from the legendary book The Pragmatic Programmer, and it still astonishes me that many programmers (even experienced ones) are not aware of it. Put simply, it suggests to write code in a way that allows future modifications be made easily. Creating mini-frameworks violates this principle in two ways:

- The mini-framework only models the current use cases to solve certain problems. When requirements change in the future, it often cannot keep up with it.

- Creating mini-framework often requires poking into the implementation details of the original framework, and those details were abstracted away for good reason: they can change at any time. The more implementation details that are relied upon, the harder for the maintaining team to evolve the original framework.

Third, mini-frameworks is a realization of the creator's mental model, but it's not everyone's mental model. People who tend to create mini-framework are often more opinionated, which is a good thing by itself. But when you create things for others to use, being too opinionated can cause problems. I would even say that sometimes (not always), creating a mini framework directly reflects the author's ego, and they chose a framework because a tiny library don't recognize the "significance of the work".

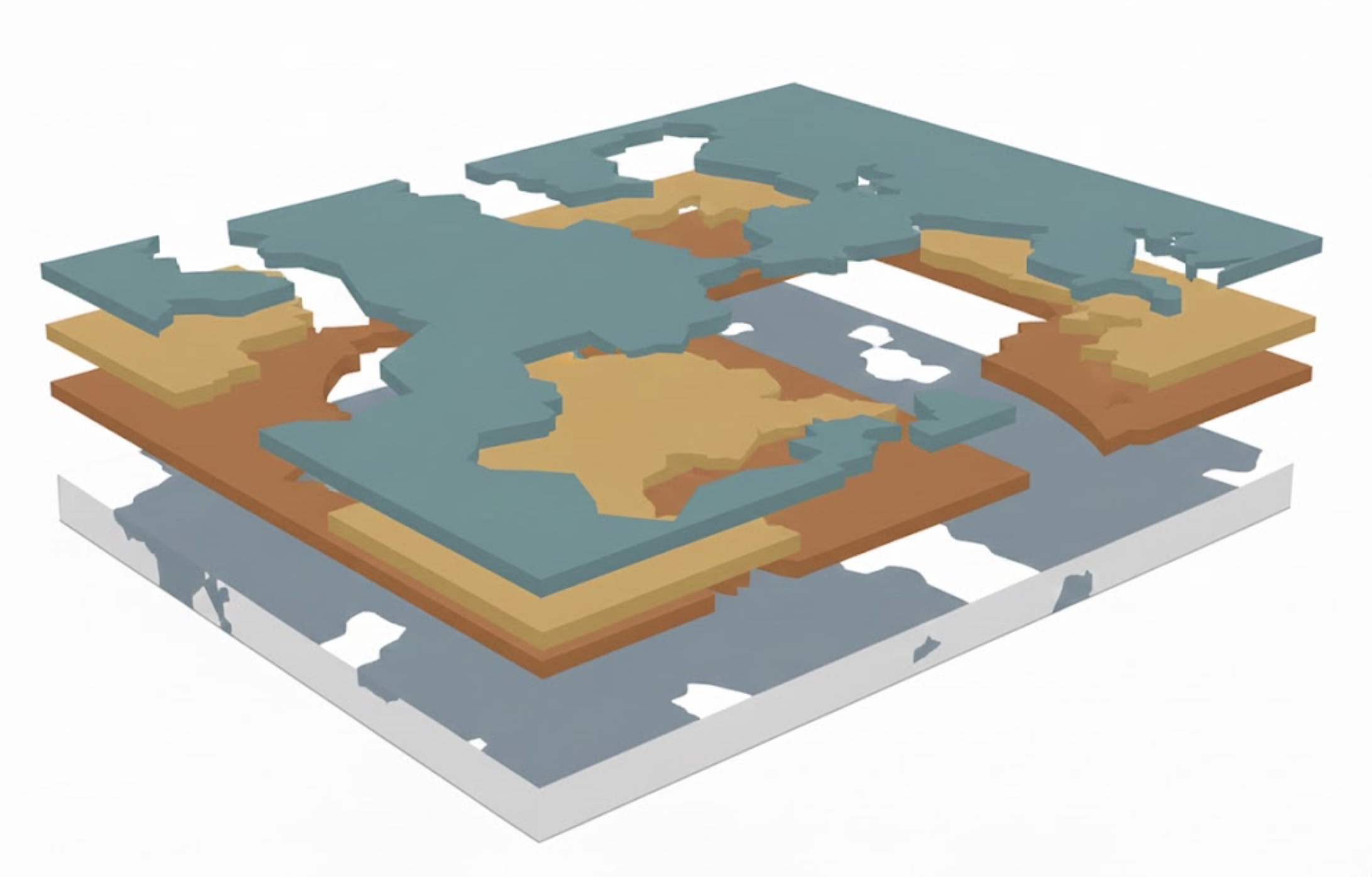

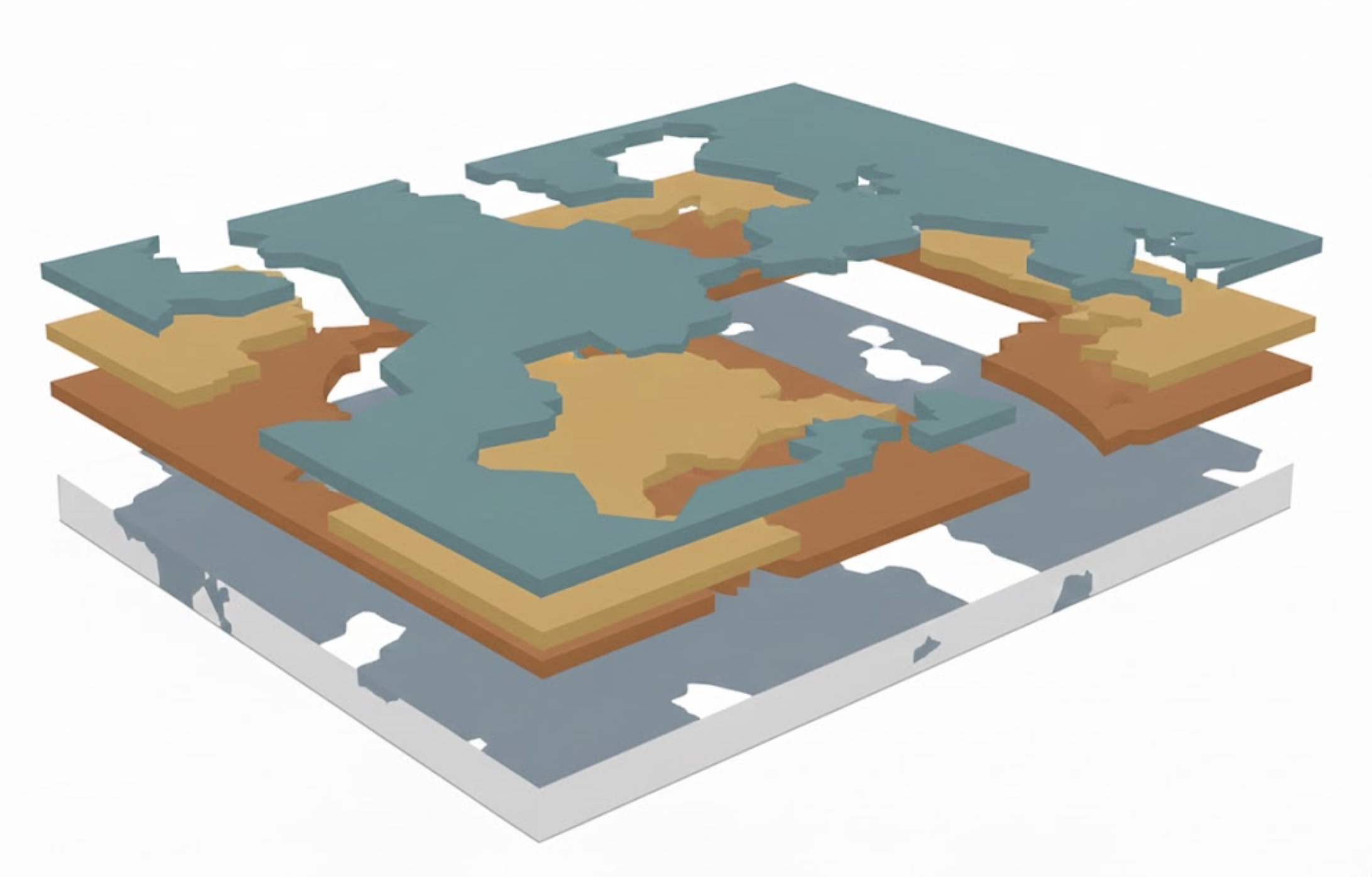

Fourth, mini-frameworks tend to cause tech stack fragmentation. I generated an image to show what I mean: part of the system is migrated, others are not. As new layers kept being added, over time it gets worse. Not sure if other companies are like this, but at Google, I've never actually seen a code migration fully complete, which is kinda hilarious.

Last but also the most concerning: lack of maintenance. Unlike shared infrastructure owned by dedicated teams, mini-frameworks were often owned by those 1 or 2 people who created it. Once they left the team or company, it becomes really hard to find successors — sure other team members may know roughly how things work, but certainly not as deep as the authors. Also, people lack the motivation to maintain existing stuff, because you don't get paid more or promoted doing this. Therefore, mini frameworks often die with the departure of the original authors, unless it has gained major adoption before that, which happens less likely than not.

So, What Should You Do Instead?

At this point, it's important to clarify what I'm against and what I'm not. I'm certainly not against adding abstractions——because abstractions are essentially, the program itself, we can't live without it. I'm against adding abstractions in a wrong way, and in the form that's not needed.

Let me bring this up once again since it's really important:

The real and only difference between a library and a framework, is whether it introduces new concepts. The line can be blurry sometimes, but more often you can tell easily. For example, a library can include a set of subclasses or utility functions around the original framework, as they don't introduce new concepts. But if you see a README that starts with a "Glossary" section, you know it's 99.99% chance a framework (people may still refer to them as "libraries", but you get the idea).

My point is, we should be really really careful introducing new concepts. If you can, avoid it. The cognitive load brought by a bunch of buzz words is heavier than people realized, and especially, what the framework author can realize. Words are the mirror of someone's thought, same with code. The authors create concepts because it is how they model the problem inside their brain, it is how they think. That's why they claim the concepts are "natural and straightforward", while others are struggling to understand.

So rule No.1, avoid creating mini-frameworks, create libraries instead. But in the cases where you do find it necessary to create a framework, my suggestions are:

Link concepts to concrete business requirements, not something in your head.

Start fresh. Don't build a wrapper around the existing framework, build your own from scratch. Yes this would make it a major decision that requires more discussions and resources, but it avoids many of the aforementioned issues. After all, you have good business justification to do this, right.. Right?

- Take it seriously. Having seen many disasters caused by mini-frameworks, I can't help thinking if it's because people didn't take it seriously enough. My feeling is that, since people don't really understand the distinction between a library and a framework, both the initiator and reviewers of the decision tend to underthink it: "Oh it's just another abstraction, we do that all the time". As my story shows, it's really not. Creating and adopting a framework, whether mini or not, is always a serious decision, thus should be treated that way. By realizing the seriousness of this matter, I hope we can avoid making rashy decisions to create mini-frameworks that should not exist in the first place.